"There's three things in this world that you need: Respect for all kinds of life, a nice bowel movement on a regular basis, and a navy blazer*." - Robin Williams

It turns out my new hospital ward isn’t a proper ward either, it’s actually the waiting area for the endoscopy patients masquerading as a ward. I’m manoeuvred into a spare space. In fact, it’s quite a large space, I’m surprised they haven’t squeezed another bed in here. I look around and assess my new cohorts, they seem quite a languid bunch. Perhaps I can enliven them by asking them if they want to join my new club? Before I have chance to acquaint myself with my new fellow patients though I hear a bit of commotion in the corridor as another bed is wheeled into our make-shift ward under protest. The new arrival sounds unhappy and is shouting something about a wheelchair. His protests however go unheeded as his bed is slid into the gap next to mine. The new patient considered his new surroundings and then looked over at me to see his new neighbour. “Hello Ken.”, I said.

Ken and I concur on the fact that the Chemotherapy Day Centre made a much better ward than the Endoscopy Waiting area. This new ward is however much better staffed with a small squadron of busy nurses and care assistants under the watchful eye of an amiable matron. I assume she was a matron, although Victoria appeared much younger than the other nurses she was certainly the matriarch of the ward and her approval and wisdom was constantly being sought.

Upon arrival yesterday morning I had had a cannula fitted in order to hook me up to a drip and it had been left in situ, presumably for easy access to my blood should they require some more. It hadn’t been used since and I suspect a fresh one would be required now anyway. It is quite uncomfortable so I had asked the nurse in the Day Centre for it to be removed, but she wanted to check with the doctor first and it never got done. I mention it to Victoria who looks at it, makes an executive decision and whips it straight out. I’ve always liked Victorias.

Once again Ken and I have arrived fashionably too late for dinner but our attentive staff are determined that our late arrival time should not impede our evening meal. A cheese sandwich is rustled up for me and hot meal that I couldn’t quite discern found for Ken. Ken is however far less concerned about his evening meal than he is with the loss of his wheelchair. He explains to each nurse in turn that he requires the wheelchair in order to get to the toilet unaided, but no one, not even Victoria, is able to find him a new wheelchair.

I text Tori the details of my latest ward so she can track me down at visiting time. The rules on visiting hours are however more strictly adhered to in the Endoscopy Waiting Area Ward and Tori barely has time for Ken to tell her about the determents of the Endoscopy waiting area compared with the palatial Chemotherapy Day Centre and the heartless confiscation of his beloved wheelchair before it’s time for her to go again.

A new male doctor greets us for the final round of the day. Ken’s up first and the curtain is drawn around Ken’s bed. I overhear that Ken’s request once again for his wheelchair goes unheeded and he is instructed to lean right forward so the doctor can examine his lower back. Ken’s protests that the pain is in his leg are soon replaced with screams of agony and a fairly accomplished set of expletives as the doctor prods and probes Ken’s lower back. “Yes”, confirms the doctor, “Definitely a back problem rather than a leg problem”. The curtain is pulled back to reveal a sullen looking Ken, still propped upright in his bed. “Sadistic bastard”, he whispers to me as soon as the doctor is out of earshot. Once again, there’s nothing much for me from the doctor, a check-up on my pain score, which I’m now ranking as about a five, a reminder to take my chemotherapy tablets and (having confessed that I have had no bowel movements since being in hospital), a foul-tasting drink to help open my bowels. I’m dosed up with enough morphine to secure me a partial nights sleep and a still fully blocked bowel by the morning.

When I wake it doesn’t feel as if last nights foul tasting bedtime beverage has had the desired effect, but ever the optimist I head off to the toilet to chance my luck. I swing open the toilet to reveal Ken proudly sat atop the porcelain, kecks around his ankles, giving it his best shot. I forgot he leaves the door unlocked to enable his chaperone to enter and convey him back to his bed, and they can sometimes forget he’s in there. I apologise and close the door immediately wondering how I can ever unsee the vision. I find an alternative toilet but to no avail and return to my bed. Thirty minutes or so later and Ken returns braced by the luckless nurse who most surely had drawn the shortest straw this morning. I really don’t know why they don’t just find him another wheelchair. “No luck”, confirms Ken as he’s bundled into the wheel-less chair beside his bed. “Me neither” I reply. After two days inside all patient conversation moves away from the weather forecast and gravitates toward the success or failure of bowel movements.

Tori arrives after breakfast and as has bought me the book from home I requested along with Ken’s morning papers. Much as I enjoy my conversations with Ken I feel I have now exhausted his repertoire and its becoming a bit like watching an old episode of Dad’s Army on UK Gold that I’ve already seen fifteen times. I’m pretty sure he doesn’t find me great company, but he does always seem very happy to see Tori when she arrives. Ken is very grateful for his morning papers. We’re reminded that it’s not officially visiting time so rather than go straight back home Tori and I go down to the hospital café for a coffee. We both order latte’s and I discover that since starting the chemotherapy I no longer appear to like the taste of coffee, but it’s a change of scenery at least.

Although I am still in pain, there seems little that can be done other than manage the pain with with a selection of semi-effective drugs, and as I can do that at home as well as I can in hospital, I might as well try and persuade them to let me leave today. When I’ve fully arranged and confirmed my escape I’ll text Tori to come and pick me up, in the meantime she heads back home and I head back to my bed. I explain my escape plan to the nurse when I get back to the ward and she recommends the palliative care nurse as my accomplice. It’s arranged for the palliative care nurse to visit me this afternoon and if she’s happy that I can self medicate then she should be able to send me on my merry way with a big box of drugs and a party sized bottle of oral morphine.

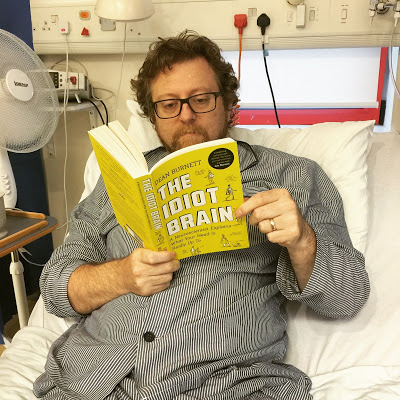

I settle into my book while I wait for the palliative care nurse to come and assess my ability to stick the right pills in my mouth at the appropriate times unaided by a trained medical practioneer. My book is a popular science book about how the imperfections of the human brain influence our experiences. It’s by a neuroscientist acquaintance of mine called Dr Dean Burnett and it has a rather gaudy yellow cover. The bright cover attracts the attention of the nurses and on their various visits each asks me what I’m reading. They all seem most impressed with the apparent high-brow level of my reading material; they clearly don’t know the author.

I’m advised by the nurses that my application for parole may be looked upon more favourably if I can convince them that my bowels are performing correctly. After checking that Ken is not absent from his bed or chair, I muster myself for one final assault on the latrine. After a few minutes of intense labouring the blockage is finally prized free clearing the way for the more free-flowing traffic that had been backing up behind. I emerge from the toilet jubilant and return to my bed. “Any luck?” asks Ken confidently noticing the grin on my face. “Oh, yes”, I say “I’d give it five minutes if I were you”. Ken extends a hand to me, I take it and he shakes it firmly, “Well done lad”.

When the palliative care nurse arrives later in the day it turns out to be just a formality. Although not as rapt as Ken, she is nonetheless pleased that I’ve had a bowel movement. After three days in hospital I’ve become quite accustomed to using the phrase “bowel movement”, even though its not the expression in my comprehensive vocabulary I usually favour for that particular event. The palliative care nurse prepares my prescription, goes through the drugs and explains the facilities of the hospice should I wish to avail myself of them. I can then collect my prescriptions from the hospital pharmacy and I’m free to go. I’m relieved and delighted to be going back home again but in a strange way I shall miss my new friends in the S.O.S. club.

* I’d say tweed jacket rather than navy blazer, but otherwise I think Robin is spot on.